Bisection is a procedure that software testers can use to isolate a defect. I’ve been having fun building a tool to assist with bisection, and I’m writing about it in order to get feedback on whether it may be useful.

This work was inspired by the “bisect up” and “bisect down” features that James Bach developed for the perlclip tool. These features are tied to the counterstring generator. You start by creating counterstrings of two different sizes (perhaps vastly different sizes), where generally you see that when you use the smaller of the two strings in a test, it passes, and you observe that a test with the larger string fails. The task is then to determine precisely where the boundary is between passing and failing. You can use the “u” (bisect up) and “d” (bisect down) commands depending on whether the last test passed or failed to generate additional test strings that bisect the remaining possibilities until you converge upon the boundary.

I’ve used this feature many times – it’s really helpful. But I often find that I get confused trying to keep track of whether I should go up or down. If I make a mistake, I have to back to the last two values I’m confident in, create two counterstrings that I don’t actually use, and start over bisecting from there.

Here is my redesign that I think makes bisection easier to do. This is implemented in testclip, my work-in-progress port/enhancement of perlclip using Ruby. I’m going to demonstrate the tool by finding a bug in Audacity (version 2.1.2 on Mac OS).

I created a new Audacity project and looked for a text field that would be a good candidate for long string testing. I clicked File > Edit Metadata and found what I needed. I fired up testclip and make a counterstring for a happy path test:

$ ./testclip.rb

Ready to generate. Type "help" for help.

cs 10

counterstring 10 characters long loaded on the clipboard

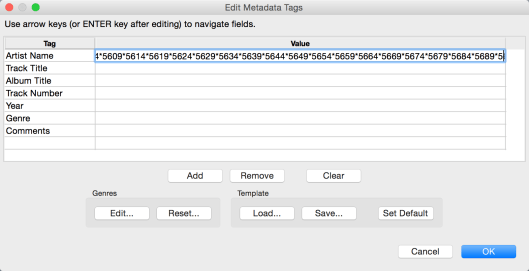

Then I pasted the data into the first field on the Metadata Tags dialog in Audacity:

I clicked “OK,” then opened the dialog again, and the data was preserved without any errors. So I established that the counterstring format is valid for this field (some input fields don’t allow asterisks or numbers, so it’s good to check). I recorded the result of the test in testclip:

pass

10 recorded as pass

That was boring. Next I wanted to try a large number. In my experience, 10,000 characters is very fast to generate, and larger than what most input fields need, so that usually where I start. I asked testclip for a 10,000 character string.

cs 10000

counterstring 10000 characters long loaded on the clipboard

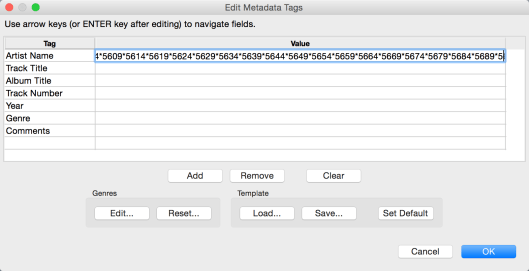

This was the result of the test:

When I tried to move the cursor further to the right, the cursor moved off the window, and I couldn’t see any more of the string. Looks like I found a bug. I record the result in testclip, choosing the tag “obscured” to identify the particular failure. This may become important later if I find a different failure mode.

fail obscured

10000 recorded as fail obscured

Due to the nature of the counterstring, I already had it pretty well isolated – it’s likely that my boundary is between 5690 and 5691 characters. But let’s make sure. I generated a 5690-character counterstring, find that it works fine, and recorded that as a pass.

cs 5690

counterstring 5690 characters long loaded on the clipboard

pass

5690 recorded as pass

I can ask testclip to report the test results it knows about and automatically identify where the boundaries between different results are.

status

10: pass

5690: pass

--boundary 1

10000: fail obscured

Next I tried 5691. This failed as with the 10,000 character string. I recorded this as the same type of failure and show the status again, which shows that testclip puts 5691 and 10,000 in the same equivalence class, just as it did with 10 and 5690 (I’m hoping it’s not confusing to call this an “equivalence class”, which is a term usually used to describe expected results, not actual results).

cs 5691

counterstring 5691 characters long loaded on the clipboard

fail obscured

5691 recorded as fail obscured

status

10: pass

5690: pass

--boundary 1

5691: fail obscured

10000: fail obscured

So, I hadn’t needed to bisect anything yet. I decided to make the test more interesting by saving the project and opening it again, to see if the long string is saved and loaded properly. I went back to 5690 and did the save and load test. Note that generating a new counterstring would reset the bisection status in perlclip, but all the test results are still retained in testclip so I can track multiple failure points. And in fact, the test fails, because after I open the saved file, the field is completely empty.

So now I abuse the tool just a bit, changing the result of the 5690 test. I’m actually running a slightly different test now, but I think I can keep it all straight. I tag this new failure “empty”. I now have two boundaries:

cs 5690

counterstring 5690 characters long loaded on the clipboard

fail empty

5690 result changed from pass to fail empty

status

10: pass

--boundary 1

5690: fail empty

--boundary 2

5691: fail obscured

10000: fail obscured

I have no clue where the new boundary 1 lies, so I’ll use bisection to find it:

bisect 1

highest value for 'pass': 10

lowest value for 'fail empty': 5690

2850 characters loaded on the clipboard

This test also failed, so I recorded the result and bisect again.

fail empty

2850 recorded as fail empty

bisect 1

highest value for 'pass': 10

lowest value for 'fail empty': 2850

1430 characters loaded on the clipboard

To complete the bisection, I repeated this process: do the next test, record the result, and bisect again. This was the end result:

bisect 1

Boundary found!

highest value for 'pass': 1024

lowest value for 'fail empty': 1025

status

10: pass

720: pass

897: pass

986: pass

1008: pass

1019: pass

1024: pass

--boundary 1

1025: fail empty

1027: fail empty

1030: fail empty

1075: fail empty

1430: fail empty

2850: fail empty

5690: fail empty

--boundary 2

5691: fail obscured

10000: fail obscured

I reported the two bugs to the Audacity project, and called it a success. Note: this was a case of a moving boundary – on two previous days of testing, the failure point was at 1028 and 1299, though within each test session I didn’t observe the boundary moving.

Besides adding the rest of the perlclip features and porting to Windows, the next things I’d like to implement for testclip are snapping the bisection to powers of 2 and multiples of 10, since bugs tend to lurk in those spots, and finishing a feature that can bisect on integer values in addition to counterstrings.

For more about perlclip, see “A Look at PerlClip” (free registration required).

photo credit: Wajahat Mahmood