In this installment of “Jerry’s Story,” we’ll take a quick look at the computer job market when Jerry Weinberg started his career, plus a peek at his first project at IBM. Refer to the home page for Jerry’s Story to see the other installments.

When Jerry applied for a job at IBM in early 1956, he was answering a job ad in Physics Today. He said this was the first computer job ad he ever saw. I found what was most likely the ad he saw, which he might have seen in either the January or March, 1956 issues of Physics Today. I looked through the 1955 and 1956 Physics Today archives and can give a bit of context around what it may have been like to look for a computer job at the dawn of the computer age.

The term “programmer” was not very common in these job ads in the mid-1950s. Surprisingly, one job ad from an unidentified company in the Gulf South region mentions programmers. It was in the context of a “computer-analyst” who is expected to be able to supervise a team of programmers for a magnetic drum computer. Other job titles that involved directly supporting or using computers included “machine operator,” “draftsman,” “engineer,” “designer,” “mathematician,” “physicist,” “scientist,” and of course, IBM’s “applied science representative.” That same unidentified company, amazingly, also asked for experienced candidates: “Knowledge of digital computer techniques desirable but not essential.” National Cash Register was looking for a senior electronic engineer with a master’s degree “and minimum of 2 years digital computer experience.”

At least one job ad didn’t make it clear whether they were talking about working with human computers or machines. In the 1950s, it still wasn’t unusual for someone to be employed as a “computer” doing manual calculations (as Jerry had done was while he was at the University of Nebraska).

The wording in the ads in this era didn’t necessarily encourage diversity. Melpar was looking for engineers, saying it was “an opportunity for qualified men to join a company that is steadily growing.” IBM, in its applied science representative ad, used phrases like “For the mathematician who’s ahead of his time…” “This man is a pioneer, an educator…” and “You may be the man….” One ad even gave an acceptable maximum age for applicants.

One mystery that remains is why Jerry hadn’t noticed a computer-related job ad sooner. I found ads for data processing and computer jobs in publications such as Scientific American and Popular Science as early as 1952. At least five different companies placed job ads that mentioned computers in Physics Today in 1955 and early 1956. One, in March 1955, was an IBM ad similar to the one that got Jerry’s attention in early 1956. Though Jerry was a voracious reader, he had missed reading about several opportunities to fulfill his dream of working with computers. We can presume that by the time he got to college, he was no longer able to absorb all available information around him like he could when he was sitting at the breakfast table reading everything on the cereal box. I did notice that the frequency of the mentions of computer jobs was much higher in 1956 than even 1955, so the odds of one of them getting noticed were going up over time.

A few ads mentioned both analog and digital computers, including ads from General Electric and Melpar. In June 1956, a Honeywell Aeronautical Division ad said, “Several unusual positions are open in our Aeronautical Research Department… Experience or interest is desirable in digital and analog computing…” Jerry’s first programming project for a client involved writing a program to replace an old analog computer.

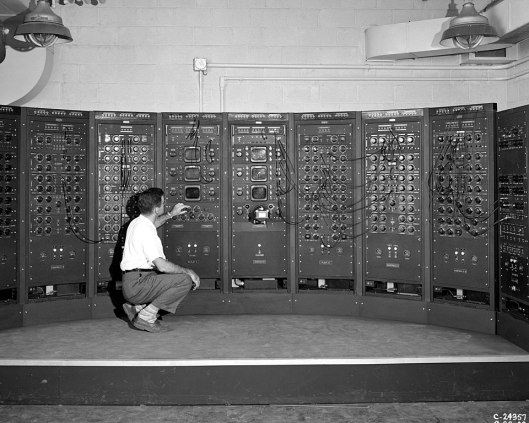

There were two room-sized electronic analog computers that were used to analyze hydraulic networks for city water systems in the U.S., one in Oregon and one in New York. They were built using resistors, and they solved systems of non-linear algebraic equations. To use one, you had to travel to one of the two locations and spend several days setting it up for a single calculation, all of which would cost thousands of dollars. IBM was tasked to replace these analog computers with a program that could run on any IBM 650.

Jerry partnered with civil engineer Lyle Hoag on the project. He said the two were essentially doing pair programming and test-first development as they replicated the analog computer’s features. Though the 650 wasn’t appreciably smaller than the analog computer, we can surmise that the program could run much more quickly and cheaply than its predecessor, and it could run anywhere there was an IBM 650 installation.

In his 2009 blog post “My Favorite Bug,” Jerry wrote about how this project produced his first and favorite bug. When the program passed all of the tests they had written, the pair brought in a small real-world problem to solve. After waiting two hours with no result, they were about to abort the program, when finally it started printing the results. This spurred them to make improvements in the program’s usability.

The experience led to Jerry’s first published article: “Pipeline Network Analysis by Electronic Digital Computer” [paywalled] (Lyle N. Hoag and Gerald Weinberg, May 1957, Journal of the American Water Works Association, vol. 49, no. 5). He hadn’t yet decided to use his middle initial in his “author name.” Jerry told me he got some unexpected fame from the article–

I had training in electrical engineering as part of my physics education, so I was familiar with networks and flow equations. As the article points out, the same program (modified) could be used for all sorts of network flow. But most of the civil engineering was provided by my partner, Lyle Hoag.

Many years later, I was way up north in Norway up in the fjords teaching a class in programming or something, and some student came up to me at the first break and said ‘Are you the famous Gerald Weinberg?’ I had published a few books by that time. I asked him, ‘Which book?’ ‘It’s not your book,’ was the answer, ‘it’s your program for hydraulic networks. Civil engineers everywhere use this, and they all know your name.’ It’s the only civil engineering paper I ever wrote. My partner became a famous civil engineer. He’s got quite a reputation; they named a few awards for him.