In this installment of “Jerry’s Story,” we’ll continue the tale of Jerry Weinberg’s education. Refer to the home page for Jerry’s Story to see the other installments.

While he was finishing his undergraduate degree in Lincoln, Nebraska, Jerry decided that he still had much more to learn. He applied to six graduate schools: Harvard University, Princeton University, Stanford University, the University of Chicago, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the University of California, Berkeley. All but Stanford accepted him and offered a fellowship. Despite getting accepted to five schools, the rejection by Stanford bothered him for some time – he was still sensitive about the awards he was cheated out of in high school. Later, when he realized how small Stanford was compared to the others, he had a better understanding of why they might not have had room for him.

UC Berkeley was his first choice, because two of his physics professors at the University of Nebraska had strong connections there. They could arrange a job for him to supplement his fellowship, and they could help him get into a program to earn his Masters and PhD simultaneously. He accepted the invitation from Berkeley. Shortly after that, he received an acceptance letter from MIT, also offering a job in their computing lab. He very much wanted to go to MIT so he could work with computers, but he was afraid that someone at Berkeley would tell MIT that he had reneged on his acceptance and then MIT would reject him. On later reflection, he realized that this thinking was naive. But he would become much fonder of the Western region of the U.S. than the East coast, so he was probably happier in California than he would have been in Massachusetts. The computers would come soon enough.

Jerry moved to Berkeley, California in 1955 with his wife Pattie. Shortly thereafter, in September, their first child, Chris, was born. They had some typical first-time parent worries. They were in what was essentially a one-room apartment, so Chris slept in a crib not far away from them. The first night they brought him home, they worried all night about whether he was still breathing. They would drift off to sleep, then both of them would wake with a start because they couldn’t hear him breathing. But he was fine – Chris kept breathing, and he slept a lot better than his parents did.

When Chris was two weeks old, they took him to a pediatrician for his first checkup. I’ll share with you the conversation I had with Jerry about how that went –

Jerry: So we go in and we had about thirty pages of handwritten questions for our pediatrician.

Danny: Oh my Lord. Poor doctor.

And they were prioritized.

Thank goodness for that.

We knew we probably couldn’t get to all of them so we had the most important one first. What do you think the first question was? Two weeks.

So many possibilities.

You’ll never guess it.

Well you mentioned breathing so I guess I just have to say, “How do you make sure he keeps breathing without staying up all night?”

No the first question was when should we get him his first pair of shoes.

Wow.

I’ll never forget this, I wish I had a video of this. And he’s this wise old guy and he says, ‘Well that’s an important question. Because you know if your kid gets to high school and he’s barefoot, the other kids are gonna mock him, it’s going to destroy him psychologically.’ I remember the answer, it was just wonderful.

Great answer!

And we just put away the rest of the questions. It was so good, that was one of the great learnings of my life.

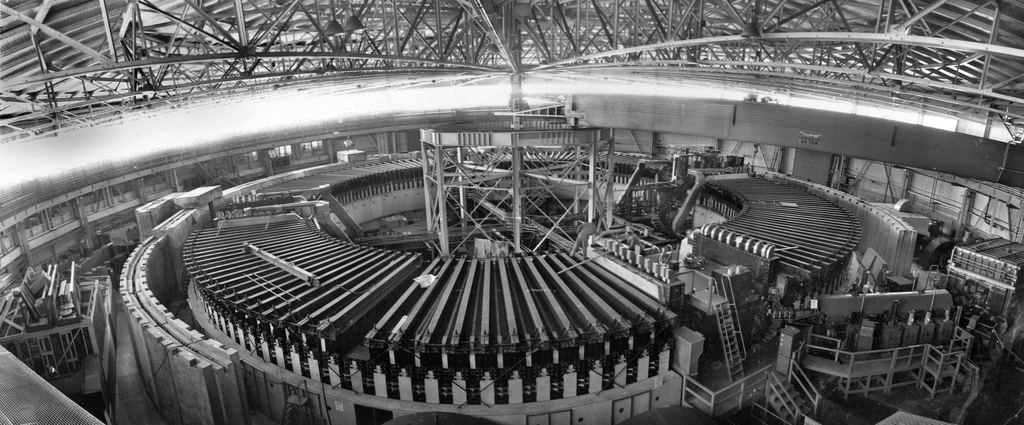

Jerry started his coursework in Physics. This included working with a particle accelerator called the “Bevatron” at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, which overlooked the UC Berkeley campus. The Bevatron had only begun operation the previous year. He set up experiments to try to simulate cosmic ray events. About 90% of the work involved stacking lead bricks to build a shelter from the particle beam. The researchers didn’t carry any kind of radiation detection with them, and Jerry worried later about whether the beam in the accelerator had caused him any harm. Records show that proper shielding may have only been installed later.

The Bevatron was used for some groundbreaking work around this same time, but we don’t know whether Jerry was involved with any of it. In 1955, the existence of the antiproton was proven using the Bevatron, which earned a Nobel Prize for two people. The antineutron was discovered there in 1956. The work for either of these could have overlapped the 1955-1956 school year Jerry was working with the Bevatron, and cosmic ray experiments like he was doing may have been relevant to the antiproton work.

Interior of the Bevatron without shielding in place, 1956. Photo credit: Berkeley Lab.

In less than a year, Jerry had passed the necessary exams and finished the experiments for his thesis, which concerned a mysterious bump in a cosmic ray energy graph. But he never finished writing his thesis. Early in 1956, Jerry saw an ad in Physics Today that changed everything for him. Here’s the text of it, in part–

FOR THE MATHEMATICIAN

who’s ahead of his timeIBM is looking for a special kind of mathematician, and will pay especially well for his abilities.

This man is a pioneer, an educator—with a major or graduate degree in Mathematics, Physics, or Engineering with Applied Mathematics equivalent.

You may be the man.

If you can qualify, you’ll work as a special representative of IBM’s Applied Science Division, as a top-level consultant to business executives, government officials and scientists. It is an exciting position, crammed with interest, and responsibility.

Employment assignment can probably be made in almost any major U.S. city you choose. Excellent working conditions and employee-benefit program.

Other ads that IBM placed that year were more clear that the job involved computers, but this one did include a picture of a computer room with a caption talking about data processing. You can imagine the appeal – the chance to finally work with computers, a promise of a good salary, and a choice of where to live. He had the right degree. He happened to be male, which the ad strongly implied was an important factor. Jerry applied for the job.

Jerry and Pattie were almost out of money. His fellowship covered his tuition. Wedding gifts and a small amount of savings were covering the rest. They had no health insurance to help pay for Chris’ birth, and now their second child was on the way. Jerry borrowed $400 from his father, the only time in his life Jerry had to borrow from him. Though they were down to their last penny, he would be able to pay it back soon.

Jerry got an offer to start at IBM on June 15. He told the university he was leaving, and his fellowship was terminated. His advisor cried after hearing the news – Jerry needed perhaps only two months more to complete his thesis to earn his doctorate. He did leave UC Berkeley with a master’s degree in Physics as a consolation prize. When I asked Jerry if he had any regrets about leaving, he answered, “only my regret that I’m finite, and can’t do everything I’m interested in.”

He had also applied for an engineering job at Boeing in Seattle, which led to a job offer from Boeing. This job did not involve working with computers, but the salary was more than twice as much as IBM was offering. Plus, he could start a few weeks earlier, which was important, because his fellowship money was gone and he was broke. But the computers were calling him. Jerry told IBM that if he couldn’t start a few weeks earlier, he would go to Boeing instead. IBM said “Yes” and Jerry accepted their offer.

It’s hard to tell whether Jerry was bluffing about going to Boeing. The part of the decision that was easy for him was leaving the university. He said, “I realized that the PhD would be irrelevant to my life, and I wouldn’t learn anything new completing the thesis. My favorite expression about education I think is by Mark Twain, who said ‘I was always careful never to let my schooling interfere with my education.'” (The Quote Investigator gives compelling reasons for why Grant Allen is more likely the originator of this aphorism.)

Going to college for him was all about what he could learn, and only peripherally about earning a degree. His desire to always be learning extended beyond his schooling. This influenced all of his decisions about how he spent his time, including his decision to walk away from a chance to double his salary at Boeing and work for IBM instead.

If he saw opportunity that didn’t involve learning, he was likely to turn it down. And if he was doing something that didn’t allow him to learn at a sufficient pace, he would tend to stop that activity. But how did he judge whether he was learning fast enough? Jerry told me, “It’s just a feeling. Like how do you know you’re hungry?”

Years later, Jerry did earn a doctorate, but that part of the story will be easier to understand after exploring his role as a programmer.

The next installment is: Computer Jobs in the 1950s.